How to – and how not to – report on sexual abuse

Photo: Davor Puklavec/Pixsell

As journalists, we always strive to tell the truth in an accurate manner and realize the words we choose affect the impression we leave on our readers, viewers or listeners. Being as fair and accurate as possible is particularly important when it comes to reporting on sexual abuse.

OnMedia’s Sean Sinico looks at responsible ways to report on rape and other forms of intimate partner violence and sexual abuse.

Journalists are used to dealing with a new topic every day when they go to work. Today it’s the city council, tomorrow it’s local business, and who knows what it’ll be the day after that. But when the task is reporting on sexual abuse and the people who’ve suffered it, journalists shouldn’t treat it like any other day at the office.

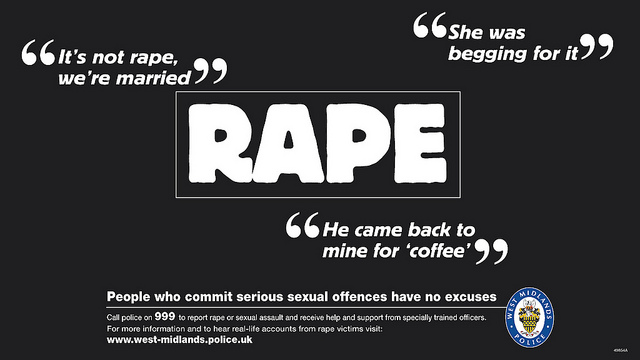

It’s easy to revictimize a person by making them relive terrible experiences for an interview and then see their lives presented in the media in a manner they didn’t want. Media reports also often make it sound like the crimes committed against the people who experienced abuse were the result of something the survivor or victim did – who they were or were not with, what they said or wore – and some reports can even imply that violent sexual abuse was actually an act of consensual sex or permissible for cultural or societal reasons.

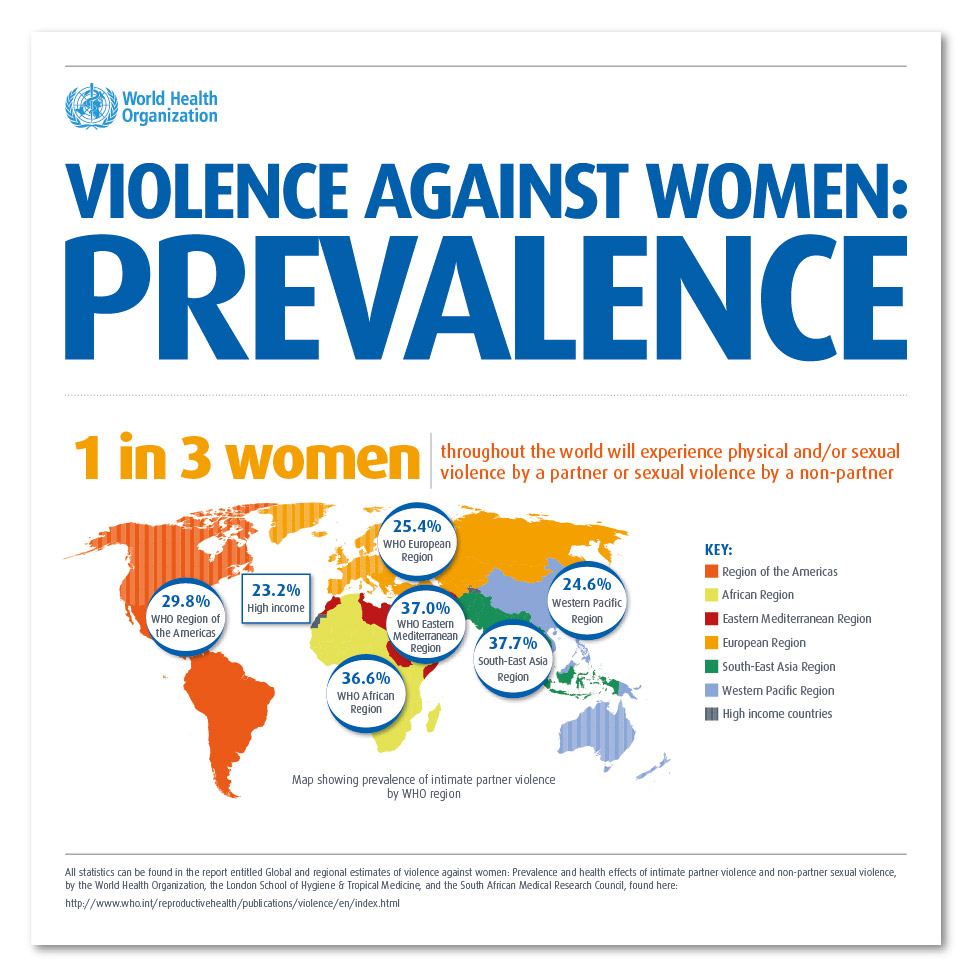

These factors all make reporting on sexual abuse difficult, but they aren’t reasons to ignore a widespread and important issue – the World Health Organization estimates that 35 percent of women worldwide have experienced either intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence. Under such circumstances, truthful and accurate reporting showing the devastating effects of rape and other forms of sexual abuse can promote positive social change at the local, national and even international level.

Here’s how you can make sure your work with survivors of intimate partner violence and sexual abuse doesn’t make a too-common problem even worse for the people already living with it.

The interview

Before starting your interview, be clear with the interviewees how what they say will be used, what type of media they will appear in, and ask if their identities need to be protected.

Listen closely to what interviewees say. You don’t want to make sexual assault victims repeat what happened to them unnecessarily. Also make sure you have a good list of open-ended questions that will allow your interviewees to share as much as they are comfortable with. Respect your interviewee’s decision not to answer questions.

The majority of females who have experienced sexual violence tend to be more comfortable with a female interviewer. If that is impossible, it is a good idea to have a female colleague present at the interview.

The majority of females who have experienced sexual violence tend to be more comfortable with a female interviewer. If that is impossible, it is a good idea to have a female colleague present at the interview.

Never say you know how they feel – even if you have suffered from sexual violence yourself. It is impossible to completely understand another person’s feelings about the violence committed against them.

Extra info: The human rights organization Witness has compiled an excellent guide and set of checklists for interviewing survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. It is also available as a printable and easier-to-read PDF.

The report

Getting it wrong when writing about survivors of violent sexual abuse is easy, and it happens too often. No matter what a person’s previous choices in life, no one deserves to be abused and nothing serves as justification for sexual abuse.

As you write, make sure to keep the following points in in mind:

Rape, intimate partner violence and sexual abuse are always crimes. In your writing, be sure to make it clear who was responsible for the criminal behavior by avoiding the passive voice, which put the focus on the victim. Clearly describe what happened. Instead of “she was abused,” you can write: “an unknown man raped her.”

You’ll need to decide how much detail of your interviewee’s experience to include in your report. It’s up to you to find the balance between providing too detailed a picture and not making the gravity of your interviewee’s experiences clear to readers.

If, during your writing, you find words like “alleged,” “admits,” “confesses,” “was raped,” “was abused,” “unharmed” or “had sex,” then you should double-check to make sure your report is clear about who the victim and who the perpetrator of the crime are. The US-based Chicago Taskforce on Violence Against Girls & Young Women has a PDF toolkit addressing exactly these phrases and what makes them inaccurate. New England Law also maintains a lengthy list of problematic language used in court documents and serves as an excellent resource of terms you should not use in your writing and suggests better alternatives that focus on the victim’s experience.

Provide context for the crime you’re reporting. Definitions of rape and sexual abuse vary around the world and reliable statistics are often hard to find because victims often do not officially press charges against perpetrators. To get a wider view of the issues, talk to health experts and NGOs to find out how widespread sexual assault is where you are, how people react to it, and how survivors cope. Painting the individual case you’re working as part of a broader social issue can help create greater awareness for sexual assault and also serve to support public health and preventative measures.

If you promised anonymity to your interviewees, make sure that there are no details in your report that allow anyone to identify them.

If you promised anonymity to your interviewees, make sure that there are no details in your report that allow anyone to identify them.

Consider including steps other victims of intimate personal violence or sexual abuse can take to find help coping with the crimes committed against them. Links to local NGOs and other resources offering support to survivors can help people find assistance they might not have known about.

Consider letting your interviewee read your report before it’s published or broadcast. This will help the interviewee know what to expect when the report is made public and can bring any inaccuracies to light.

More information

This is the place where I’d generally give you links to excellent reporting on sexual abuse. Such examples, however, are difficult to find. In a 2013 interview, Claudia Garcia-Rojas, an editor of the Chicago Taskforce media toolkit linked to above, said she looked at hundreds of articles about rape and sexual assault for positive example and found two, which “weren’t even about rape, they were stories about covering rape.”

My own searches were equally unsatisfying, so instead of positive examples, I’ll ask you to read through the links above – even if you don’t think rape or sexual violence is a topic you’ll have to cover. The tragic spread of sexual violence means at some point in your career – whether you expect it or not – you’re certain to come in contact with a victim of sexual violence, and you owe it to that person to have an idea of how to handle the situation.

If, in addition to the links above, if you’d like more in-depth information on reporting on sexual abuse, check out the Poynter News University course Reporting on Sexual Violence and its 2009 webinar Covering Sexual Assault. The Scottish charity Zero Tolerance has created a PDF document covering in more detail many of the topics addressed in this post.

** For information on where victims of intimate partner violence or sexual abuse can turn to, the HotPeachPages website maintains an international list of abuse and crisis hotlines.

RELATED ONMEDIA POSTS

Interviews – talking to a genocide survivor

Bloodshed in the news – dealing with graphic images

Author: Sean Sinico, edited by Kyle James

Image credits: flickr/Lucy Maude Ellis CC:BY-ND; WHO; flickr/Women’s eNews CC:BY, flickr/West Midlands Police CC:BY