Get smart about getting hacked!

Watch out! Someone could be spying on you

When hackers broke into AP’s Twitter account earlier in 2013, their fake tweet about Barack Obama being injured in an explosion at the White House caused the US stock market to plunge. Just before the Twitter account was hacked, AP staffers had received an email asking them to click on a link that supposedly went to a Washington Post article.

Although it looked legitimate, the email was actually a phishing attack (view the email here). The fraudulent link redirected the recipients to a bogus site where they were asked for their login credentials. At least one person fell for the phishing email and gave the hackers, the Syrian Electronic Army, the password they needed to tweet in AP’s name.

In this case, the incident proved more embarrassing than damaging – the tweet was corrected immediately and the stock market recovered within minutes.

But falling for a phishing attack can have much more serious repercussions.

In Bahrain at least 11 people were imprisoned between October 2012 and May 2013 after the Bahraini government successfully phished their identities. All had allegedly written anonymous Tweets criticizing Bahrain’s King Hamad. The authorities identified the individuals by sending them fake links from Twitter and Facebook. When they clicked on the link, spy software noted the computer’s IP address allowing authorities to track the Twitter users down (read how the Bahriani government did this in an extensive report by Bahrainwatch.org).

Phishing attacks don’t just have to come from Twitter or email though; from sms to Skype, What’s App or even via the comments box on an online article, fake links can be embedded in any kind of communication.

What’s more, phishing doesn’t always involve a fake link. It might contain a downloadable file containing malicious software (or malware) that installs itself on your computer or smartphone without your knowledge.

Renowned security expert Jacob Appelbaum tweeted earlier this year about discovering spyware on the computer of an Angolan activist. Installed when an email attachment was opened, the spyware took shots of the victim’s screen and copied his files, automatically sending the information to remote servers.

This particular spyware wasn’t very high-tech but other malware can log keystrokes to steal logins and passwords, record visited websites or even activate the camera or microphone on the laptop to record what people are doing.

We journalist are used to receiving emails, tweets or Facebook messages with links to stories or documents. After all, being on top of the news is part of our jobs. But letting hackers, whether they are government authorities or criminals, steal our information can endanger not only our stories, but also ourselves, our colleagues and most importantly, our sources. That’s why it is essential to be aware of the problem.

Here are a few tips:

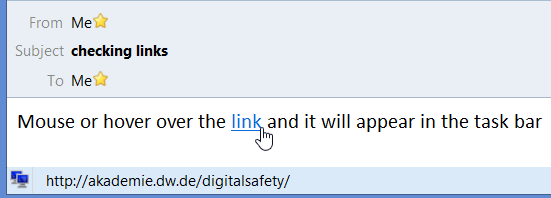

Mouse over the link. You can view a link’s URL by hovering over it with your mouse (but don’t click). If the URLs doesn’t look legitimate, or doesn’t match the one given in the email text, don’t open it.

Mouse over the link. You can view a link’s URL by hovering over it with your mouse (but don’t click). If the URLs doesn’t look legitimate, or doesn’t match the one given in the email text, don’t open it.

Read the URL carefully. Fake links will often try to trick you into thinking the URL is real by using similar spelling to a real site, for example www.aljazera.com instead of the correct www.aljazeera.com. If you don’t look carefully, it’s easy to think you’re clicking on a legitimate link.

Check the domain name. The domain name is the part of the URL just before the first slash. For example, Deutsche Welle’s domain is www.dw.com. Genuine DW links have the domain name before the first slash – for example, http://akademie.dw.com/digitalsafety/ is still a genuine DW URL as the “dw.de” is before the first slash. A phishing URL to a fake DW site may look like this www.topstories.com/dw/globalization. Here’s a great spambusters post that tells lets you know more about checking links.

Use an URL checker. They aren’t foolproof but sites such as safeweb.norton.com are a good start.

Don’t open unverified attachments. All file types can contain malware. If in doubt, delete.

To find out more about avoiding hacking attacks, tune into the What’s in that message live online session with security expert Morgan Marquis-Boire on December 6 at 4pm CET. It’s just one of six online sessions happening during the “Digital Safety for Journalists” Open Online Workshop running from December 2-6. Other live sessions include mobile phone safety and using the Internet without being tracked.

Organized by DW Akademie together with Reporters Without Borders, the online workshop is free and open to anyone. For more information, visit the Digital Safety for Journalists website where you’ll also find daily posts on the topic starting from November 25.

Otherwise check out the Rory Peck Trust website which has fantastic online digital security resources written specifically for freelance journalists. For more about malware, see the entry How can I avoid malware.

Written by Kate Hairsine and edited by Kyle James

Feedback