Checking the lies – the global fact-checking explosion

There’s a boom in fact-checking sites seeking to combat misinformation and untruths spread by public figures. In 2014, new initiatives popped up as far afield as Uruguay, Turkey and Ukraine.

There’s a boom in fact-checking sites seeking to combat misinformation and untruths spread by public figures. In 2014, new initiatives popped up as far afield as Uruguay, Turkey and Ukraine.

The latest Fact-Checking Census compiled by the Duke University Reporters’ Lab has counted 64 active fact-checking sites around the world. That’s massive growth compared to a year ago when the census found 44 active sites. (Some sites are only active during election years, so the Fact-Checking Census counts both active and inactive sites.)

The vast majority of dedicated fact-checking initiatives are in Northern America and Europe, the census found – although there are now five in Latin America, five in Asia and one in Africa.

Internet breeds spin

The explosive growth in fact-checking is an attempt to keep public figures honest and inform citizens, said Bill Adair, professor of journalism and public policy at Duke University and co-author of the 2015 Fact-Checking Census.

“Technology is now allowing politicians to make political statements directly to mass audiences in ways that were never before possible,” he told onMedia.

“And with that comes much exaggeration and many falsehoods, making fact-checking more important than ever,” said Adair, who created the influential US fact-checking site, PolitiFact, in 2007.

Truth squads shooting down lies

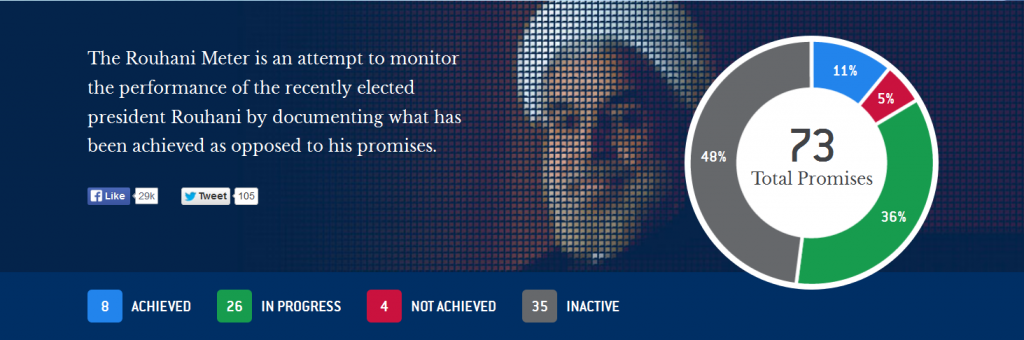

Some of the fact-checking sites included in the census focus exclusively on scrutinizing politicians’ statements. Others track the pre-election promises of elected politicians, such as the Rouhani Meter in Iran.

Others are broader still in scope. Africa Check, for example, picks apart statements made by politicians, public figures and the media while StopFake exposes Russian propaganda about the events in Ukraine.

This kind of fact-checking typically involves vetting claims, which usually include some kind of numbers or statistics, made by public figures. It often means meticulously combing through various statistical sources and research papers as well as seeking a range of expert opinion about how reliable the sources are, and talking to someone who can explain what the data actually means. (For an example of a report incorporating these aspects, see Africa Check’s Does South Africa really have the largest security force in the world?)

There’s fact-checking and fact-checking

The kind of fact-checking done at these new dedicated sites is quite different from the fact-checking done internally at some magazines and newspapers, where in-house researchers verify the accuracy of information, such as people’s names and job titles (and much more interesting facts) as well as make sure a source really said what they were reported as saying.

Let’s say, for the sake of an example, in-house fact-checkers might verify if the Deputy Minister of Correctional Services in South Africa actually said, “You find that there is better medical facilities given from government in prison than out there [outside the prison].”And if he did say it, it then they’ll move on, job done.

But what these in-house fact-checkers traditionally don’t do is scrutinize the truth of the statement itself – is it actually true that there are better medical facilities in prison than outside prison in South Africa? And with media organizations groaning under the burden of 24-hour news-cycles and dwindling budgets, it’s often unlikely that a reporter will take the time to analyze such a statement either.

This is precisely the gap that the dedicated fact-checking sites are often filling. (And in case you are wondering, the statement about prison health services, according to Africa Check, is exaggerated.)

There’s evidence fact-checking sites are having an impact. Former Florida governor Jeb Bush recently hesitated to cite a figure in case he was “PolitiFacted”, while a 2013 study found politicians in the US were less likely to fib if they knew they were being fact-checked.

“These results suggest that the electoral and reputational threat posed by fact-checking can affect the behavior of elected officials,” Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler wrote in the report by the New America Foundation.

“In this way, fact-checking could play an important role in improving political discourse and strengthening democratic accountability.”

Fact-checking takes time

For those contemplating starting up such an organization, Africa Check director Peter Cunliffe-Jones says it’s important to “respect the amount of work” it can take to check a claim.

For those contemplating starting up such an organization, Africa Check director Peter Cunliffe-Jones says it’s important to “respect the amount of work” it can take to check a claim.

“Some of the fact-checking reports take three weeks,” he told onMedia. This is partly due to the problems of finding reliable information in Africa.

“Data can be incomplete, partial or old, or people refuse to release it,” he said. This is even the case in South Africa, where Africa Check is based, despite the country having some of the best available data on the continent.

Because of the time and effort involved, Cunliffe-Jones believes it’s more effective to pay professional journalists to do fact-checking rather than rely on volunteers, as some sites do.

This, however, means finding money to pay salaries – not always an easy endeavor.

Chasing the money

While some fact-checking initiatives are affiliated with TV stations (such as Australia’s FactCheck), or with newspapers (such as Brazil’s Preto No Branco), other initiatives operate as independent non-profits.

Despite the different set-ups, one thing they have in common is that “no one has found a sustainable business model for fact-checking,” Duke professor Adair wrote after a fact-checking summit in London in 2014.

“So the big challenge around the world is how are we going to pay for this journalism,” Adair told onMedia.

According to him, fact-checking just doesn’t generate the volume of page views that can sustain it as stand-alone journalism, leaving many initiatives dependent on external grants from international foundations.

Africa Check, for example, originally started with seed money from Google. It now has several different funders, but as director Cunliffe-Jones puts it, “if one of those organizations pulls out, then all of a sudden you have a crisis.”

Africa Check is looking to become less dependent on external funding by generating revenue through crowdfunding and research consultancy.

In fact, for director Cunliffe-Jones, it’s important to really think through the funding model before starting up any new fact-checking initiative.

These onMedia posts might interest you, too:

Ukrainian fact-checking site debunks propaganda

Several of the fact-checking sites have great tools to help you do fact-checking on your own. See Africa Check’s How To Fact-Check or StopFake’s How To Identify A Fake.

Written by Kate Hairsine, edited by Kyle James