Independent election reporting in Sierra Leone

The elections in Sierra Leone in November 2012 marked another important test for the country’s democracy and stability some ten years after the end of its civil war.

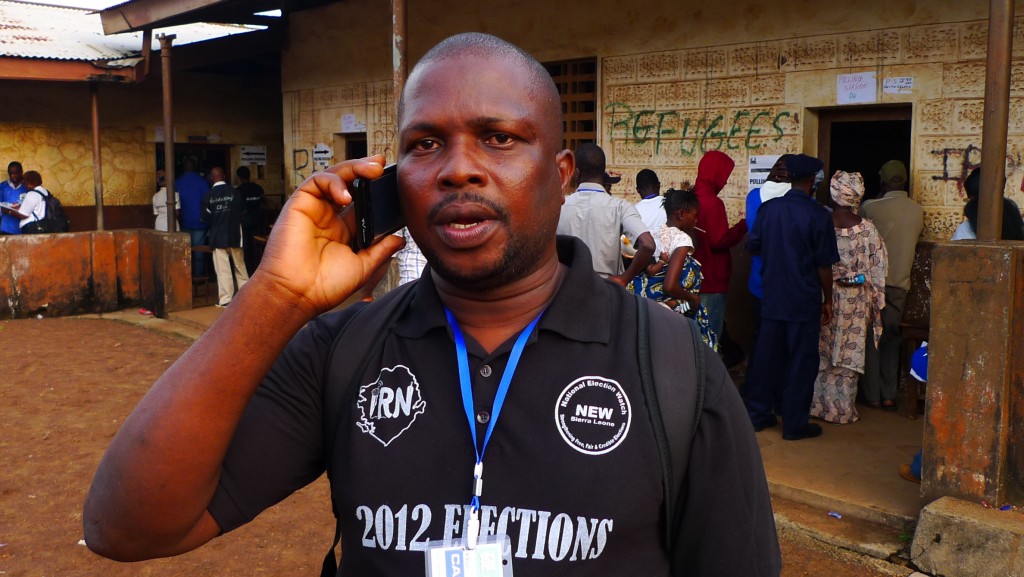

To help provide accurate and impartial coverage of the elections, local radio stations and international partners worked together to produce IRN – the Independent Radio Network. This temporary cooperation gave many Sierra Leoneans across the country access to up to date and independent election reporting. DW Akademie’s Kate Hairsine was one of the international trainers mentoring IRN journalists and looks back on how this innovative network covered the elections.

Even in the middle of the night, the sounds of the Independent Radio Network (IRN) blared though the bedroom window of my guest house in Freetown. It seemed simply everyone in Sierra Leone with a radio was tuned to the network in the lead up to the 11 November 2012 elections.

Whether I was eating breakfast at a backstreet cafe, catching a minibus or buying bananas at the markets, IRN’s theme song blasted my eardrums from first thing in the morning to deep into the night.

Walking down a potholed road on the way to buy some food one evening, I met Umaru Karoma, who like a lot of people in Freetown had a radio glued to his ear. I recognized IRN’s theme song straight away.

“We are all listening to IRN,” Umaru said. “Everybody wants to know about the elections.”

Radio vital for information

Radio is the most important medium of communication in Sierra Leone. One of the poorest countries in the world, it has a high illiteracy rate and newspapers are virtually unobtainable outside of the capital, Freetown.

To make the situation even more difficult, although the media in Sierra Leone is relatively free of government interference, it is extremely difficult for Sierra Leoneans to access impartial and credible information. This is because many of the newspapers and radio stations are biased towards one particular party or another.

As for the public TV and radio broadcaster SLBC, the European Union Election Observer Mission (EUEOM) noted that it gave “access to political parties and candidates through free-airtime programmes”. However, in news bulletins and election related programming “SLBC showed biased coverage in favour of the ruling party” – the APC.

Hence, the Independent Radio Network filled a vital role. IRN was originally established back in 2002 to cover that year’s national elections. It’s primarily funded by international donors and the network has developed a reputation for producing independent and unbiased content.

Covering the country

Together with two other trainers from DW Akademie, I worked with IRN journalists for two weeks helping them with producing and planning their election coverage. And all three of us were incredibly impressed by the quality of IRN’s election programming and the effort they took to ensure their reporting was accurate and balanced.

And the hub of this exceptional reporting was the tiny, cramped and hot IRN studio in the center of Freetown.

Normally, IRN preproduces three hours of weekly programming for distribution through its 28 partner stations across Sierra Leone’s 14 districts. But for the elections, IRN ramped up its programming to broadcast live, around the clock, from election eve until the day after elections. It then reported live three times a day until results were announced six days later on November 16.

This was a mammoth undertaking that was two years in the making, involving hundreds of reporters in the field, as well as a multitude of hosts and producers.

For the first time IRN joined forces with Cotton Tree News, a news and information service with its own partner stations. The temporary partnership meant around 90 percent of country had access to the live IRN radio coverage, making it akin to a national broadcaster.

Roving reporters

Pivotal to IRN’s election coverage were the 630 roving reporters from the partner stations to monitor selected polling stations across the country – effectively to be the “eyes and ears of the nation”. Each reporter was equipped with Le 200,000 ($45) and 250 units of phone credit. In the lead up to the elections all of the reporters attended election reporting training and were also given a copy of IRN’s excellent Reporters Handbook.

Starting from election day, the journalists called in to the central hub and reported on all the election day processes: whether a polling station opened up on time, if voting was running smoothly, if people could vote freely or if all those who wanted to vote were able to by the time the polling station closed.

And for some of the reporters, simply getting to their allocated polling station was a grueling exercise. Sulaiman ‘Storm’ Karoma from the IRN partner station, Radio Democracy, spent two days traveling to the remote village of Yiffin in the northern Koinadugu District. The final 50 kilometers of his journey involved a tortuous six hour motorbike ride down a washed-out muddy track.

Karoma says it is was “important” he was sent there because he provided eye-witness information from somewhere where there were no national or international observers.

According to Karoma, the polling station opened late because the truck carrying elections materials got bogged and the materials had to continue on motorbikes. Some ballot boxes were missing for part of the day as were screens for the polling booths.

“It is incumbent on us as journalists to have an idea of what it is like at a particular place during elections,” he said when he returned to Freetown. “That is the first time that a reporter has been sent there and a lot of people want to hear from places that are excluded.”

In the 2007 elections, IRN had a pool of 420 reporters. According to IRN coordinator Ransford Wright, having such a large number of reporters for the 2012 elections was “a major advantage” because it meant being able to get updates from all over the country.

Quashing rumors

Because of a transportation ban on election day, journalists couldn’t use minibuses or okada motorbike taxis to move around as usual (most journalists in Sierra Leone rely on okadas to get around).

This meant every journalist who was able to beg or borrow a car or motorbike was roped in to be an ‘on call’ reporter, who sped to a polling station when there were rumors of tension or wrongdoing. That way, IRN could double check the situation on the ground for themselves before going to air with a story.

This is especially important in a society where rumors often play a big role in inflaming tensions.

Team effort

Back at the IRN office in Freetown, at any one time, dozens of journalists crowded around a giant table, writing radio scripts, ringing potential interview partners and editing reports. Down one side of the cramped room, producers manned the four telephone lines – one for each of the country’s four districts.

The IRN producers worked furiously to coordinate the information coming in and organize the programs. IRN’s election coverage was also supported by BBC Media Action and Search for Common Ground, an international NGO dedicated to peace-building.

The IRN producers worked furiously to coordinate the information coming in and organize the programs. IRN’s election coverage was also supported by BBC Media Action and Search for Common Ground, an international NGO dedicated to peace-building.

Amara Bangura, from BBC Media Action, said the whole coverage was “strengthened” as a result of so many people working together.

“If you can divide the job … at the end of the day you put together everything and have an amazing program.”

And in a boost for all of those who worked on IRN’s election project, the Commonwealth election observers noted in their official report that although “most of Sierra Leone’s media was openly partisan”, IRN “provided impartial news and information on the election.”

Feedback