Digital detectives fight photo manipulations

Ever since photography was first invented in the 1800’s, people have been doctoring images. From the army exaggerating military victories to dictators removing political figures who have fallen out of favor, photo manipulation has a long history. To give a recent example, North Korea released a photo of a military exercise showing hovercraft landing on a beach. But the eagle eyes of Alan Taylor from The Atlantic detected that several of the hovercraft were surprisingly similar to each other. It seems somebody with a penchant for copy and paste button had increased the size of the fleet.

It isn’t the first case of visual armament and it won’t be the last. Especially as manipulating photos has never been so easy. Although many doctored images may look clumsy like the hovercraft photo, there are countless image editing tools and apps out there that allow even amateurs to create changes which are almost undetectable to the eye. This is a huge problem for media organizations who are increasingly using images on social networks in their news reporting. And it seems even professional photojournalists can’t be relied on to resist the temptation to pimp their photos with Photoshop.

But how can media outlets ensure that a photo isn’t a fake? This is where computer specialists like Hany Farid come into play. Farid is a professor at Dartmouth College in the US, and a digital forensic scientist who advises media organizations and intelligence agencies on a photo’s authenticity. Farid is also involved in the Silicon Valley company, Fourandsix Technologies, which has released software that can check whether a photo has already been processed in some way. This is an incredibly challenging feat of computing that evaluates numerous parameters. In an interview with DW Akademie’s Steffen Leidel, Farid says even with such software, there will never be 100 percent protection against fake photos.

The digital era has ushered in an endless range of possibilities to edit pictures. Image manipulation is available to everyone. Is this the end of trust in news photos?

We have to acknowledge that we have been manipulating photographs for a very long time. For example, if you go to our website, you will find something called “Photo Tampering throughout History”. Manipulating photographs dates back to the 1800s. Now you made the valid point that what used to be less the norm is becoming more the norm. Everybody now has a camera and everybody has fairly sophisticated computing power in form of a laptop, tablet or a smart device. Everybody has access to sophisticated photo editing software. Now we have seen a democratization of the ability to alter photographs.

We have to acknowledge that we have been manipulating photographs for a very long time. For example, if you go to our website, you will find something called “Photo Tampering throughout History”. Manipulating photographs dates back to the 1800s. Now you made the valid point that what used to be less the norm is becoming more the norm. Everybody now has a camera and everybody has fairly sophisticated computing power in form of a laptop, tablet or a smart device. Everybody has access to sophisticated photo editing software. Now we have seen a democratization of the ability to alter photographs.

Whether this means the end of trust is a good question. What it means is that we now have a different relationship to images. Previously photographs were a recording of events. We treated them as such without a lot of skepticism even though there was photo tampering throughout history. But I think now we need to have more skepticism. I think we can still trust but we should ask some questions. This can be in the form of the type work of we do in forensic analysis. It can be in the form requesting multiple images. One of the great things about everybody having a camera is when world events break, you don’t get just one or two images. You get thousands of images. One way of regaining trust is by simply having redundancy in the system, having a thousand independent people photographing the same event. Then it is hard to argue that all the images are fake.

Your company Fourandsix has developed the image authentication software FourMatch. What exactly does the software do?

FourMatch is a very simple forensic technique that determines if an image came directly out of the camera or mobile device or tablet and didn’t undergo any other changes. That means it wasn’t uploaded to a social networking site, didn’t go into photo-editing software and didn’t go into photo management software. Nothing happened to this image. When a camera creates a JPEG image, it packages this image in a very specific way that is distinct to that particular camera. And when software or online services modify or touch the image, they change the packaging.

So FourMatch can read more than the EXIF data or metadata (information about the image that your camera automatically records with the image file)?

The metadata and EXIF data capture quite a bit information about the camera. The data tells you what the focal length was, if the flash fired, the time and date and maybe the GPS. But the problem with only looking at this information is that it is very easy to add after you have modified the image.

Rather, what I’m talking about is how the actual JPEG image is stored in the camera. Engineers make a number of design decisions about how they are going to compress an image using the JPEG standard. There are hundreds of parameters that need to be set by engineers. The good news about this is what we look at with this software is fairly distinct to each model and it is difficult for the average person to modify after the fact.

How does that help journalists or news organizations who want to verify photographs?

If an image comes from a citizen journalist or a photographer, you can just ask one simple question: does this come directly out of the camera? This is a very strict criterion of course. If somebody just puts the image into iPhoto and then exports it, it will not appear to be an original even though nothing has happened to the image. Obviously we can change or alter images without changing its contents, like cropping, increasing the brightness or the contrast.

I tell organizations like AP or Reuters, have your photographers submit the original photograph plus whatever they then want be published: crop, color adjusting, contrast adjusting. Then you have to decide. You can make the comparison because you have both images. Knowing that the original has to be submitted keeps people in check. If you know that you have submitted the original photograph to me, I’m far less likely to go crazy on the photograph to make it more artistic. So there is a simple way to solve that problem.

I tell organizations like AP or Reuters, have your photographers submit the original photograph plus whatever they then want be published: crop, color adjusting, contrast adjusting. Then you have to decide. You can make the comparison because you have both images. Knowing that the original has to be submitted keeps people in check. If you know that you have submitted the original photograph to me, I’m far less likely to go crazy on the photograph to make it more artistic. So there is a simple way to solve that problem.

But where would you draw the line between editing an image and image manipulation? Recently, there was a heated discussion about whether the winning image for the 2013 World Press Awards had been excessively altered.

It’s an interesting question – what does it mean to alter a photograph? If you remove something from a photograph or if you add a person or an object, clearly this a manipulation. However, it depends on the context. If you are a photojournalist in a war-zone, it is clearly photo manipulation. If you are a fashion magazine and there is something in the background that you don’t want and you remove it, nobody is going to complain about this. The context of the photograph matters tremendously.

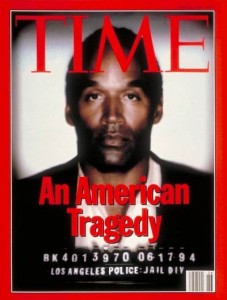

Many years ago here in the United State, O.J. Simpson was on trial for murder and Time Magazine ran a photograph on the cover where he was very dark. They were accused of racism because they made him look darker and blacker and meaner.

That’s a really interesting example because something as simple as just darkening an image can make it look more menacing. You see this also in war photographs. If you take a war photograph and you just increase the contrast and darken the image, things like smog and fire can look much more menacing and damaging. In other cases, darkening and contrasting the image has no real impact on your overall interpretation of it.

That’s a really interesting example because something as simple as just darkening an image can make it look more menacing. You see this also in war photographs. If you take a war photograph and you just increase the contrast and darken the image, things like smog and fire can look much more menacing and damaging. In other cases, darkening and contrasting the image has no real impact on your overall interpretation of it.

The New York Times recently put a photo edited by Instagram on its front page and it has also published photos altered with the Hipstamatic App. Some argue this is not truthful photojournalism anymore.

Again, context matters. The fact is those apps are fairly limited in what they can do to an image. They are not going to remove something or add something to an image, it is simply an overall effect. In some cases, that’s enough to distort reality, in other cases it isn’t. We have to acknowledge that Instagram and Hipstamatic are not qualitatively different than a camera. Cameras do not take perfect recordings of physical events in the world: there are transformations. They sharpen the image, there is contrast enhancing going on, there are all kinds of digital manipulations happening in the phone. They are not as extreme as Instagram and Hipstamatic but there are manipulations happening. What we are talking about is a question of degree, not a question of ‘yes’ and ‘no’. So does it cross the boundary? I would say sometimes ‘yes’, sometimes ‘no’.

Associated Press has the rule for its photographs: no filters. Could this be a solution?

This is a perfectly reasonable policy. What we are going to see as time goes on is mobile devices taking over. This means the types of very sophisticated photo editing that now reside within Photoshop are eventually going to make their way into apps and there is going to be a time in which we can do more than just filter. On a mobile device, we are starting to do fairly sophisticated things. And eventually that would become fully automatic and that leads to a very different question – what does it even mean to take a picture? On a mobile device, you can take multiple images and it automatically stitches them together and gives you a wide-angle image. That’s an image that the camera is creating for you, you didn’t photograph that. It’s a mild manipulation but it is a manipulation. Things are complicated now and I think it’s fine to say, “OK: no filters”. But we have to think forward in time a little bit.

This is a perfectly reasonable policy. What we are going to see as time goes on is mobile devices taking over. This means the types of very sophisticated photo editing that now reside within Photoshop are eventually going to make their way into apps and there is going to be a time in which we can do more than just filter. On a mobile device, we are starting to do fairly sophisticated things. And eventually that would become fully automatic and that leads to a very different question – what does it even mean to take a picture? On a mobile device, you can take multiple images and it automatically stitches them together and gives you a wide-angle image. That’s an image that the camera is creating for you, you didn’t photograph that. It’s a mild manipulation but it is a manipulation. Things are complicated now and I think it’s fine to say, “OK: no filters”. But we have to think forward in time a little bit.

Is there the perfect manipulation that even you can’t detect?

Yes, but I’m not going to tell you what that is. I have definitively seen some very good fakes. One of my favorite ones was a photo of US Vice President Biden without a shirt washing a Trans Am. It was incredibly well done but we found inconsistency in the lighting. We have to acknowledge that this technology can’t detect every possible alteration under the sun. This is very similar to the issues of spam versus antispam, virus versus antivirus. We can go a long way to making it difficult, time consuming and requiring expertise to create a fake. But the very nature of what we do means there will always be somebody – I’m frankly one of these people – that create fakes that are essentially impossible to detect. That’s the nature of the business we are in.

Yes, but I’m not going to tell you what that is. I have definitively seen some very good fakes. One of my favorite ones was a photo of US Vice President Biden without a shirt washing a Trans Am. It was incredibly well done but we found inconsistency in the lighting. We have to acknowledge that this technology can’t detect every possible alteration under the sun. This is very similar to the issues of spam versus antispam, virus versus antivirus. We can go a long way to making it difficult, time consuming and requiring expertise to create a fake. But the very nature of what we do means there will always be somebody – I’m frankly one of these people – that create fakes that are essentially impossible to detect. That’s the nature of the business we are in.

Hany Farid’s profile site at Dartmouth College

Fourandsix’s blog about photo manipulation

Feedback